Yes, the Baltimore Orioles Just Won 101 Games

It’s about 6:15 in the morning on October 4th, 2016. My dad had (unforgivably) sent me to bed after 4 innings of the Orioles vs Blue Jays wild card game. I had gone to sleep feeling anxious, but hopeful that my O’s could exit the hostile Rogers Centre environment with a W and a ticket to play the Texas Rangers in the AL Divisional Round; After all, Mark Trumbo had hit a two-run shot down the left field line to put us up 2-1, just minutes before I heard the dreaded “alright pal, time to head upstairs.” My legs shook as I crept downstairs and into the kitchen. I opened my mom’s laptop, searched “mlb scores," covered up the score with my left hand so I didn’t know who won, clicked on the 7 minute highlight video, and watched nervously. And lo and behold, in the bottom of the 11th inning, Edwin Encarnación drilled a walk-off three run blast off a meatball from Ubaldo Jimenez to sink the Orioles 5-2.

And that was it for the Orioles, whose entire 2016 roster is a thing of the past now. For the next five years after that fateful evening in Canada, Baltimore’s record was 253-455—good for worst in the league in that span. The Orioles were garbage. They were the laughing stock of the league. I reached a point early in the 2022 season when I didn’t think I’d ever experience the level of happiness for the Orioles that I did when we reached the playoffs in 2016 against the New York Yankees. Until last Thursday night.

First, we have to go back to 2018. Baltimore had gone 75-87 in 2017, and had missed the playoffs. By the trade deadline, there was a gigantic cloud of gloom over the organization. Practically every member of the roster was overpaid. Chris Davis was making $23,000,000 per year to hit .168. Adam Jones was being paid $17,333,333 to be a middle of the pack batter. Alex Cobb and Andrew Cashner took up another $20,500,000 and a combined ERA of 5.10. And Mark Trumbo, the man who had led the MLB in home runs in the Orioles wild card season was unrecognizable in 2018 despite his $12,500,000 paycheck. The one man who was not overpaid was their star player—Manny Machado—who wanted nothing more than to leave Baltimore. And in the blink of an eye, Machado, an MVP threat every year he was an Orioles, was gone.

The Orioles traded their franchise cornerstone to the Dodgers, and in return they received Yusniel Díaz, who never once played in the big leagues, Rylan Bannon, who had 21 career plate appearances, two double-A assignments, and an interesting prospect named Dean Kremer—a 22-year old pitcher who had spent his last couple of year pitching for the Tulsa Drillers. More on Kremer later.

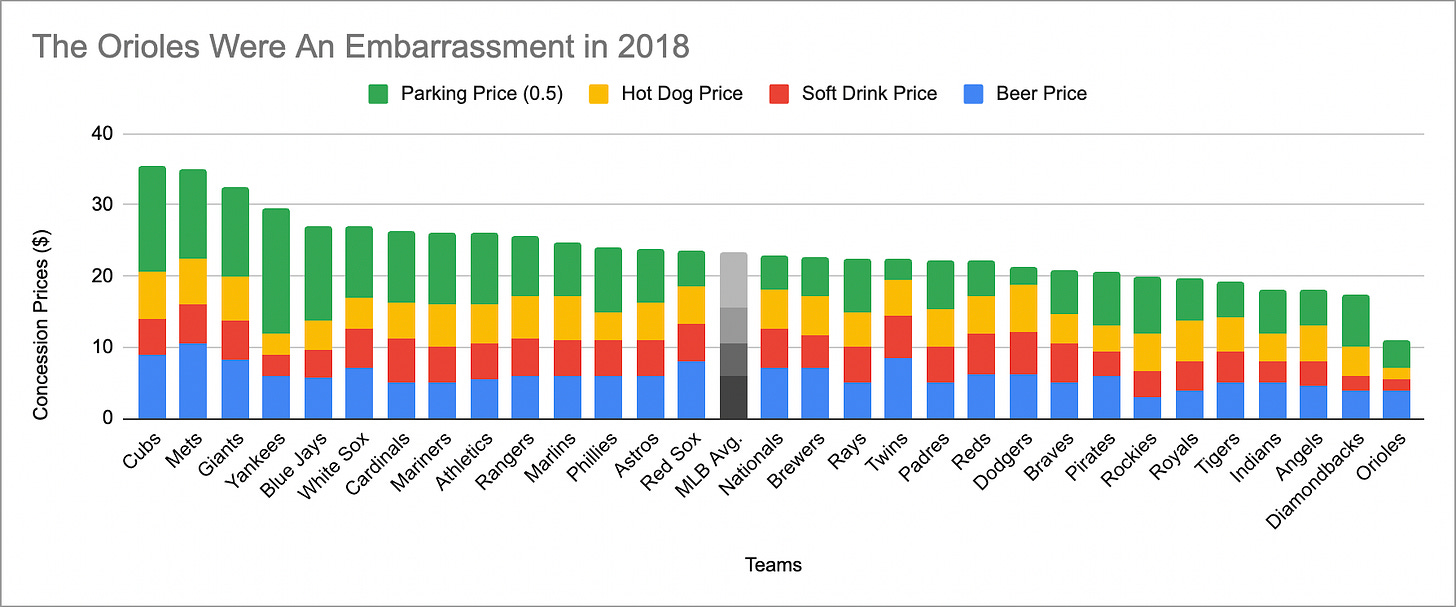

Several other important players including Jones, Kevin Gausman and Jonathan Schoop would dealt away as well, creating an inevitable end to the tenure of Dan Duquette as the GM. As expected, finances tanked. Although they had cut their payroll by a significant amount, ticket and concession prices and attendance were down by a drastic amount. No one wanted to come to games to watch Trey Mancini and Craig Gentry. In the third home game after Machado’s departure, Orioles vs Rays tickets went for as low as $8. I bought a bowl of macaroni and cheese for 12.99 the other day. Think about that. Overall, even with Machado there for most of the season, The Orioles average ticket price was just $29.95. The average premium ticket price was $51.87. For perspective, the Yankees average premium ticket price $346.53. As for concessions and parking expenses, this is all you need to see.

And as for attendance, an average of just 44.1% of Baltimore’s stadium capacity was filled. No one wanted to come to Orioles games anymore; their glory days—which were making it to the divisional round—were far behind them. They would finish with a record of 47-115, good for worst in the league and the franchise’s 123 year history, as well as the 15th worst in the modern era (1901).

By 2019, the ownership and management had no hopes of winning games. Players that would never or barely play major league ball again after their Baltimore days like Stevie Wilkerson, Rio Ruíz, Chance Sisco, and Renato Núñez were regular starters. To understand the disparity between the 2019 roster to past rosters, Baltimore’s payroll was just $73,000,000—third to last in the league. In 2018, their payroll was $150,000,000. As for the actual product on the field, Baltimore had the worst pitching rotation in recent memory. Their ERA for the year was 5.59 which was the ninth worst figure of all-time. It reached a point where I would be genuinely excited to see that we had held teams to five runs. Meanwhile, the Dodgers allowed 3.80 runs per game in 2019. At the plate, the Orioles were 21st, 24th, 24th, and 25th in AVG, OBP, SLG, and OPS, respectively, leading to a 54-108 record. Even worse for the team, attendance had declined by another 18.5% with even lower ticket prices.

Yeah, that’s how bad it was. And that was just your average night at Camden Yards. Maybe 1,000 fans in the stadium by the 9th inning.

Thus, at the center of the Orioles’ failure was the topsy-turvy ownership situation they found themselves in. Peter Angelos, who was a former lawyer and member of the Baltimore City Council from 1959-1963, had been the Orioles owner since 1993. We already mentioned some of the questionable financial decisions made by Angelos regarding contracts, but in February of 2019, MLB commissioner Rob Manfred told the Orioles organization that they had until June to inform the league who was controlling the team—Peter’s health was failing him at 91 years old, so many of the daily operations were delegated between his two sons, John and Louis. There was no clear owner in Baltimore, explaining the mess that the team was. This was only the beginning of the disagreement between the Angelos sons, who would have a major dispute who would keep their father’s assets.

Once Peter Angelos became too ill to manage his law firm in 2018, he handed the reigns over to Louis. In late January of this year, Louis accused John and Georgia Angelos (Peter’s wife) of taking money of Peter’s account in an effort to support John’s law firm.

“In an amended complaint filed last month, Louis Angelos escalated his claims and accused John and Georgia of siphoning tens of millions of dollars out of Peter Angelos’s personal bank account in an effort to shield the money from potential creditors connected to a pending malpractice lawsuit against the law firm” (The Daily Record).

The two brothers filed numerous lawsuits and complaints against each other. Inside of one lawsuit was Louis’ accusation of John, saying that John planned to move the team to Tennessee if he gained control.

In 2021, when Louis filed another suit against John and Georgia for moving more money out of Peter’s account in order to shield potential creditors stemming from the lawsuit of John’s firm. Georgia was on record saying that Louis was “unable to live up to his father’s expectations or win the approval (he) desperately craved.” Now, John is the CEO of the Orioles and Louis runs the law firm.

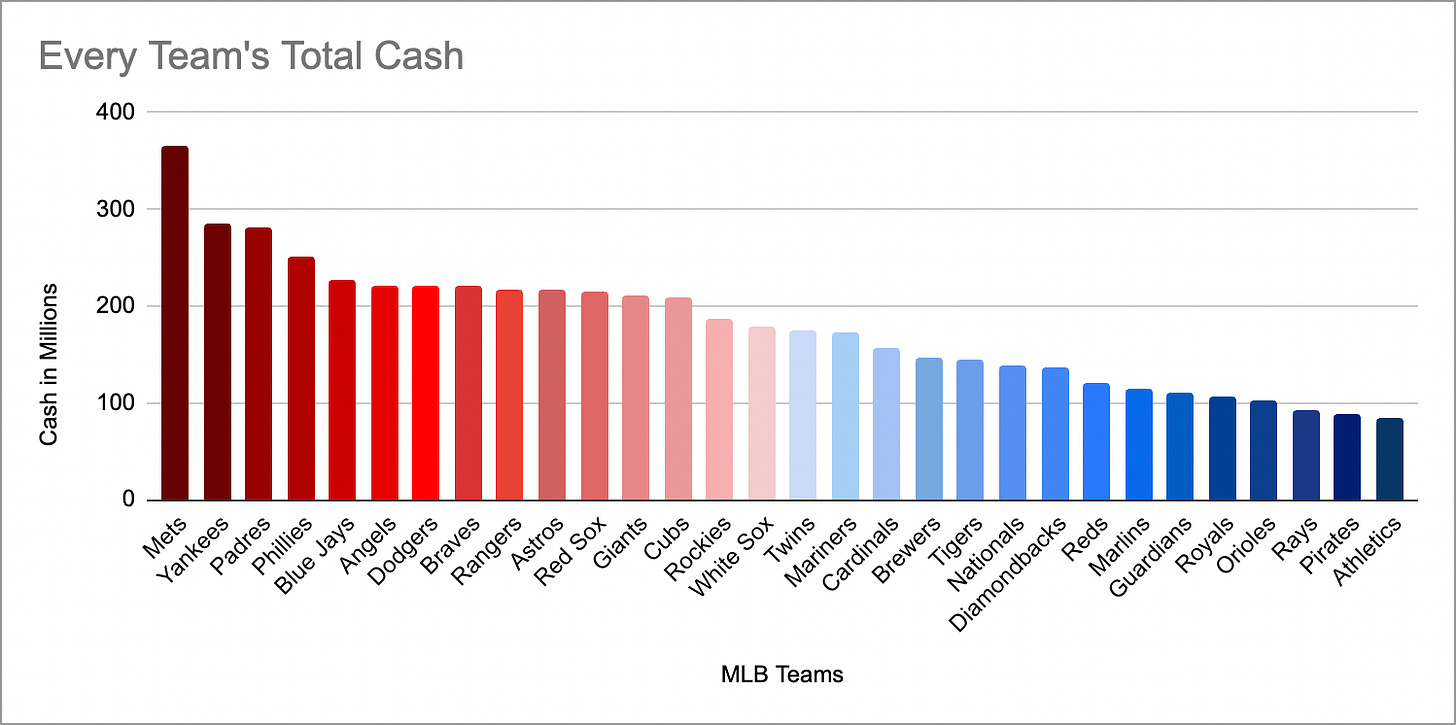

Even with the Orioles newfound success in the 2023 season, the Angelos brothers refuse to spend big on free agents and great players and had the third shortest payroll this year. A perfect example: Rather than targeting Justin Verlander, Max Scherzer, Jordan Montgomery, or Marcus Stroman at the trade deadline, they acquired a mediocre starter in Jack Flaherty. Despite being left out of Bleacher Report’s five smallest market rankings this year, the Orioles were 27th in total cash rankings. It doesn’t sound like a lot, but it’s actually very difficult to have discrepancy between market size and total cash.

The Orioles payroll was just $71,000,000 in 2023 as well (somehow lower than they 2018 season.

Now, back to the misery.

Things weren’t much better in 2020 when the Orioles went 25-35 and missed the playoffs again, and 2021 was more of the same. They beefed up their ticket prices by 29.40% (15.5% higher than the next team) despite tying for the worst record in the league at 52-110. By now, watching Encarnación send my team home in the 2016 Wild Card game was a distant memory. I wasn’t sure if the team that I has relentlessly followed since 2014 would ever get out of the pit of tanking. Even worse, I could feel myself distancing from the team as a fan because I was so sick of losing.

This is the point where we have to understand that baseball is more than just a game played between the lines. Baseball is a business—one in which you cannot prosper without tireless negotiation and scouting, financial willpower, up-to-date strategy, and calculated prediction. Behind closed doors, the Orioles were plotting. Using draft capital, and what has turned out to be far and away the best farm system in the MLB, the Orioles were building a young powerhouse, that will be feared for years to come.

Jul. 8-10, 2015 — In the 2015 draft, the Orioles needed more dynamic hitters with speed, and positional versatility. They found two diamonds in the ruff at the 36th pick in Ryan Mountcastle and Cedric Mullins who went in the 13th round.

Aug. 4, 2016 — The Orioles traded for a young pitcher from the Miami Marlins farm system. His name was Félix Bautista and he was just 21 years old. Bautista would not be an immediate option for Baltimore, as he spend years bouncing around between the Dominican Summer League, Delmarva, Bowie, Norfolk, and Aberdeen.

Dec. 8, 2016 — In the 2016 Rule 5 draft (a draft of players who are not on a 40-man roster, the Orioles had the 18th pick, and selected Anthony Santander. Santander would hold a spot on the major league roster, but didn’t play 100 games for the next three years.

Aug. 10, 2018 — Cedric Mullins made his major league debut, and compiled 3 hits, 2 RBI’s, and a run.

Nov. 16, 2018 — After firing Dan Duquette as GM, the Orioles hired Mike Elias to restart the franchise. Elias is, formerly, an executive for the Houston Astros. A Yale graduate, Elias was mentored by Jeff Luhnow, a longtime Cardinals’ scout. When Luhnow was hired as the GM of the Astros in 2011, Elias went with him as his special assistant. In 2011, the Astros were 56-106, just 9 games better than the Orioles in 2018. In the next two years, Houston won 55 and 51 games. In Elias’ time there, The Astros took Carlos Correa first overall in 2012, and Alex Bregman in 2015—both of whom were fundamental to the Astros four World Series’ appearances since 2017. And by the time Elias was hired as the GM of the Milwaukee Brewers in 2016, the Astros were an 86-win team, and poised for their aforementioned success. Elias begun his tenure in Milwaukee with a 68-win team and transformed them into a 98-win team in 2018. Bottom line: Mike Elias knew that the best rebuilds happen when teams hit rock bottom. There’s no room to flounder in a sea of unknown; the only direction to go is up He also understood that analytics are the future of sports, and that they should not be neglected in spite of the common belief that the eye test is the best test. And that’s exactly what he did with Baltimore.

Jul. 17, 2019 — The Orioles had the first pick in the draft for the first time since 1989. They selected Oregon State catcher, Adley Rutschman, and picked third baseman Gunnar Henderson in the second round. Like Bautista, Rutschman and Henderson worked their way through the minors in two and four years, respectively.

Dec. 4, 2019 — The Orioles dealt way failing pitcher, Dylan Bundy, for Isaac Mattison, and three minor league players. One of those players was pitcher, Kyle Bradish.

Aug. 21, 2020 — Mountcastle made his major league debut, recording a hit. Nine days later, he hit his first big league home run. The following year, he would lead all rookies in home runs.

Nov. 18, 2021 — Mullins finished ninth in MVP voting, and earned a silver slugger award.

Apr. 10, 2022 — Bautista made his major league debut and recorded his first career save in a 5-3 win over the Cardinals.

These signings and debuts are fun and all, but every team goes through these motions of having successful young players. By May 21st, the Orioles season appeared lost once again as they sat last in the AL East with a grizzly record of 16-24. And then it happened. In hindsight, it was one of the greatest things to ever happen to Orioles baseball this century, but we had no idea at the time. On that Tuesday in the middle of May, Rutschman—one of the best prospects in years—made his MLB debut. Baltimore’s 1-6 loss to the Rays didn’t mean much at the time because everyone could see that Rutschman’s unbelievable talent. Since he joined the team (281 games ago), the Orioles have not been swept, and have a record of 167-114. In the 281 games prior, Baltimore was 101-180.

Let’s talk a little more about Elias and the front office. Sig Mejdal was a biomathematician for NASA in the late 1990s. While working for NASA, Mejdal had a side job as the chief quantitative analyst for Sam Walker's fantasy baseball team Streetwalkers Baseball Club. Walker would eventually write a book about Mejdal’s revolutionary, numbers-based methods. This would help Mejdal earn a job in the analytics department (sabermetrics specifically) for the St. Louis Cardinals in 2005—when his career with Elias would begin. He was promoted to senior quantitative analyst in 2008 and director of amateur draft analysis in January 2011, and in the time between his hire and 2012, no team had more draft picks that became big league players than the Cardinals.

Have you ever seen Moneyball? The 2011 film highlights the Athletics magical 2002 season. Billy Beane, the A’s general manager at the time, had just lost his three best players in the smallest market in the league by a landslide. His scouts were looking for replacements with arm talent, attractiveness, and whether or not a player’s game was flashy. That’s when Beane hired Peter Brand—a Yale economics major—whose philosophy was about finding the players who were the most undervalued. Oakland couldn’t afford to pay anyone major money, and instead dished out small contracts to guys who play the game ugly (lots of walks, biggest strength is clean fielding, etc.), and might have defects (past injuries, weird pitching motion, etc.). For Brand, it was all about the numbers. It’s safe to say that Brand’s plan was a success—Oakland won 103 games that year.

Since that season, analytics have been the driving force for putting together the best teams, making Mejdal’s ideology more valuable over time. Elias brought Mejdal with him with to Houston, where he created an accurate algorithm that predicted player performance compared to their market value, and created a STOUT system which basically turned a player into a number. Funnily enough, Jeff Luhnow, Elias’ mentor, called Mejdal his “moneyball stat guy.”

When Elias was hired to Baltimore in 2016, Mejdal came with him and became Elias’ assistant GM (the same role that Peter Brand played to Beane in 2002). As you saw in one of the graphs earlier in the article, Baltimore is the 4th smallest market in the league, so they also couldn’t rely on big free agent signings. Using Mejdal’s deep analytical background and Elias’ rebuilding experience, the Orioles worked around this and were starting to pull off a clinical rebuild.

Rustchman finished second in the rookie of the year race in 2022 despite missing 25% of the year.

Henderson was awarded team MVP in 2023 and is the clear frontrunner for AL Rookie of the Year.

Kyle Bradish made his debut late last season, and is 4th in ERA (2.83) amongst all AL pitchers.

The Orioles traded for Yennier Canó in August of 2022. He had a 9.22 ERA last year, but has a 2.11 ERA and an all-star appearance this year..

Félix Bautista is unfortunately out for the season, but has been one of the best closers this season with a 1.48 ERA and 33 saves.

Anthony Santander has been the best player in the 2016 Rule 5 draft.

Young pitching prospect, Grayson Rodriguez, looks to be a developing ace.

Jordan Westburg and Heston Kjerstad look like strong prospects, and Jackson Holliday, one of the greatest prospects of the last decade, is poised to make his debut soon.

The Orioles finished their 2022 campaign as one of the most surprising teams, winning 83 games. This season, they were projected to finish last in the AL East, but Mike Elias trusted his formula, and let his birds fly.

The Orioles started out looking like the 83-79 team from last season. But when May hit, the bats got going, and the pitching surprisingly started ramping up. On July 20th, the Orioles beat the Rays, and secured sole possession of first place in the AL East as well as the entire conference. Once they got over that hump, Baltimore never looked back, and the team projected to win 74 games was, all of a sudden, on a historic pace for the franchise. On September 17th, the Orioles won their 93rd game of the season, and clinched a playoff spot for the first time in seven years. The only thing left to do was lock up the division and the 1-seed.

September 28th was the most important night in Orioles history since that fateful Wild Card game in 2016 Baltimore was sitting at 99 wins (the franchise’s highest win total in 44 years), and was one win against the frisky Red Sox away from locking up the 1 seed for the first time since 1997. Baltimore triumphed in a 2-0 victory behind 5.1 shoutout innings from Dean Kremer—the very man who the Orioles traded Machado for at the start their treacherous rebuild.

Mejdal’s analytical perspective had worked. A team that was plagued by highly overpaid players just five years ago now had a perfect balance of underpaid players who fit together perfectly on and off the field. And contrary to teams like the Padres, Mets, and Yankees, the Orioles didn’t fret about not having a superstar player. They felt that they had more talent between all 40 guys on the roster than any other team.

The Orioles had the second best record in the entire league, and yet, Adley Rustchman finished highest on the team in jersey sales with a ranking of 20th amongst all players.

Mullins makes $4.1M. Austin Hays, their all-star outfielder who we haven’t even mentioned yet, makes $3.2M. Mountcastle, Rutschman, Henderson, and Kremer are still making under a million per year. The 74-87 Mets had a payroll 4.84x more expensive than the 101-61 Orioles. And somehow, the Orioles $71M payroll this year is less than the $73M, 54-108 team from 2019.

Elias, Mejdal, and Orioles manager Brandon Hyde at Camden Yards.

Now, I’ll say this. I do not expect the Orioles to win the World Series. The Braves are a buzzsaw. I trust them to make it past the ALDS—they are better than the Rays and the Rangers. However, the Twins are on a hot streak and are built for the postseason, and no team is more experienced than the Astros. The ALCS might be were the Orioles magical run comes to an end. But either way, this season is just the beginning of something great. This team will continue to have success and will only get better. Unlike the A’s in 2002, this is not Mike Elias’ last gasp attempt at winning a title. This team is young, built for the future, and shows no signs of slowing down. The Orioles’ rapid ascendance from rock bottom to the top of the league will be the blueprint for rebuilds for a long time. They’ve got something special brewing in Baltimore.